4 Common Change Models and How Useful They Are at Work

Project managers deliver change all the time, but in my experience, we aren’t always focused on the change side of change… if you see what I mean.

Project managers tend to focus on the delivery and execution, and hopefully there’s a change manager who picks up the impact on the end users.

But if there isn’t, then you need to spend at least a little time on making sure your project changes land well. Employees experience change in different ways: some embrace it, while others resist.

Whether it’s a new software rollout, a company restructure, or a shift in business strategy, change requires people to adapt both emotionally and structurally. And that can be hard.

The change models

As part of my mentoring training, I looked at four well-known change models: Kubler-Ross, Bridges, Lewin, and Kotter, and their relevance to workplace change. While some models focus on the emotional journey individuals go through, others provide structured processes for leading change successfully.

Both approaches are worth taking into account when you’re preparing for project delivery, because we need to acknowledge that people are emotional beings who also have to change the way they work as a result of our projects.

So, for project managers and team leaders, understanding these models can be invaluable. Knowing more about them can help you tailor your stakeholder engagement and help you decide on management strategies for leading the project.

1. Kubler Ross

You’ve probably seen the Kubler Ross change curve, it’s the one of the popular

The challenge to the Kubler Ross model is that it was designed for people who are grieving, and therefore they are starting in a very different place to individuals who are going through organizational change. It’s useful, but I think we should review it critically when considering it in the light of personal development.

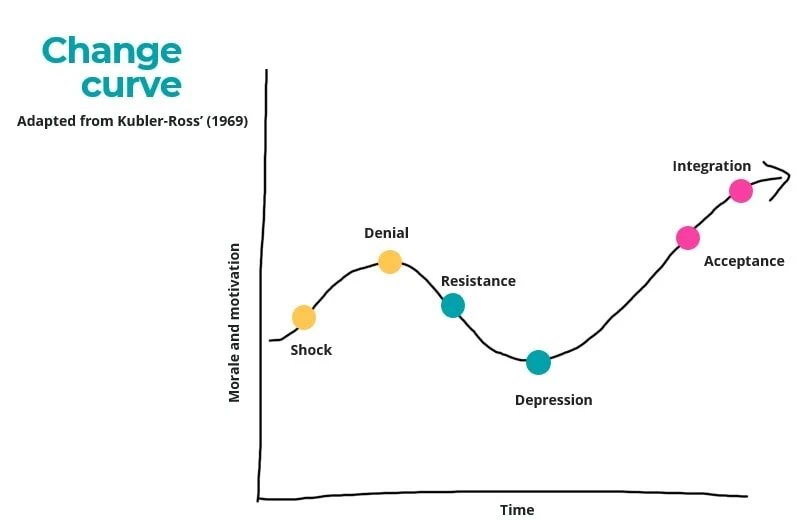

The Change Curve is the version that is used for organizational change and is based on Kubler-Ross’s work in the 1960s.

It is not a smooth curve because people go through ups and downs in dealing with change and the emotions associated with it. The commonly-acknowledged steps are:

- Shock

- Denial

- Anger

- Depression

- Acceptance

- Integration

This is different from the original work into grief which only had 5 steps, and the change curve seems to have various variations as it has evolved or been put to different uses over the years.

I think people can move through some of the stages quite quickly. Reflecting on this, I did not think that I had personally acknowledged ever feeling denial at work for example, following the shock of an announcement like a redundancy programme, but reading more about it, denial shows up as questioning the decision and thinking that there is no need for change, and I have definitely done that.

Once that stage is passed, people feel suspicious, isolated or worried. It takes time for acceptance and integration and understanding that others feel the same way and that they are not alone is helpful.

Best for: Understanding individual level feelings related to change. However, you need employee feedback to be able to act on it – if no one shares how they are feeling you’re kind of flying in the dark.

2. Bridges Transition Model

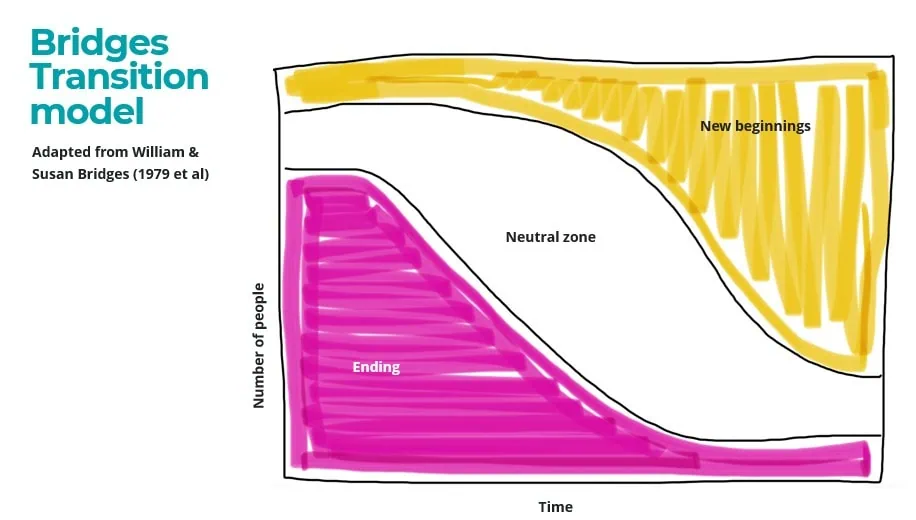

Bridge’s transition is similar to Kubler Ross in that it considers the emotional journey people go through.

There are three phases:

- Ending

- The Neutral Zone

- New Beginning.

The way the three phases are described graphically in the image below shows that people take different lengths of time to come to the new beginning and accept the change they have been through. Some people never get there.

Example:

When we launched a new software system in my old job, the people who could not get on with it were eventually let go as it was a requirement of their role to be able to operate the new software. This is a final resort, as ideally we would be supporting and mentoring people through the change so they come to the new beginning in a reasonable amount of time.

What I like about this model is that it makes evident the transition. The change is what is done to people (a new leader, a merger, a process change etc). The transition is the personal journey that people go through to make peace with the change. We can influence how quick the journey is by recognising what has been left behind and supporting people to let go of what has been and manage the confusion and potential distrust of what is coming to land safely in the new beginning.

Best for: I think this works well for large-scale changes like operational restructuring.

3. Lewin

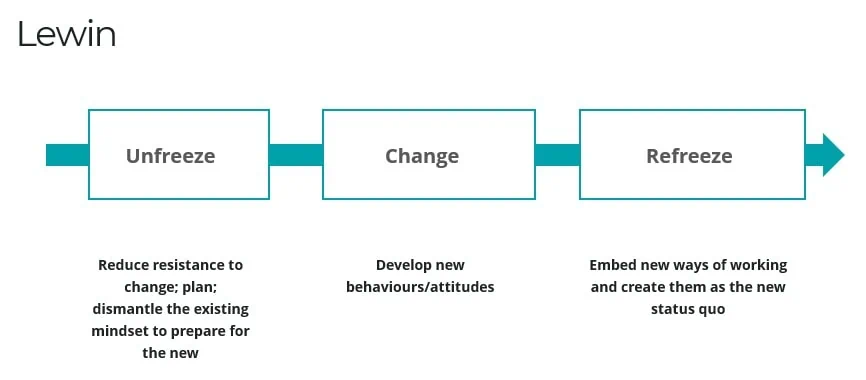

Lewin’s model is one that is taught in project management but it’s less about the emotional journey that people go through (like Kubler-Ross and Bridges) and more about the process of creating that emotional journey by structuring the experience that people go through.

The steps are:

- Unfreeze

- Change

- Refreeze

I like this as it’s really simple and it shows the need to ‘break’ old behaviours in the Unfreeze stage to make space for the change. The change itself is surrounded by activities that support behaviour change to ensure people are brought along with the change.

Best for: I think this approach works well for continuous improvement. You can use it on a small scale to talk about incremental changes.

4. Kotter

Kotter is an 8-step change management approach that again focuses on the process for an organisation to deliver change rather than the emotional journey that an individual experiencing change goes through.

However, it does prompt reflection and action on the personal experience as part of the process as without that, the change will most likely fail. It’s a very structured approach.

The steps are:

- Create a sense of urgency

- Build a guiding coalition: this is a network of super users or change champions

- Form a strategic vision: I think it’s important to do this first actually, as otherwise what are you creating a sense of urgency about?

- Enlist a volunteer army: this step is about empowering people to rally around the opportunity and decide actively to commit and contribute to the change. In my experience, we don’t always do this because we aren’t creating the kind of change that needs a grassroots movement to support it.

- Enable action by removing barriers

- Generate short-term wins: in our projects, we do try to have short-term wins because they keep momentum going and create stories that we can share to encourage others or to continue the support for the project.

- Sustain acceleration: this is just doing more of the same so you get more wins.

- Institute change: this is about embedding the change so it becomes ‘how we do things around here’ and the normal ways of working.

I think Kotter’s change model is worth knowing but feels over-engineered for most small scale project change.

For project team members, it’s probably a bit overkill too, as individuals would be part of the organizational change but aren’t typically leading it so would not be working through these steps. It’s got to be led at organizational level.

I think you’ll need strong commitment to this as a leadership approach with buy in from the top if you want to adopt Kotter in its purest sense.

Best for: Kotter is useful for addressing employee resistance and changing company culture.

Practical ways for project managers to use these models

Here are some ways that you can use these models in real life as part of project management process.

Offer perspective

Sometimes I have been through a similar change in the past. One of the steps in Kubler-Ross is the anger/depression stage and it can help people get through that stage if they know that others are feeling the same way.

If I can share my personal perspective as a mentor or project team leader (of this change or a similar change I have been through previously), it may help my colleagues realize that they are not alone.

Offer a safe space to reflect

People might not be open to talking to business leaders about what’s bothering them, but they might talk to you.

I had an email exchange with a colleague recently and she had been offered a new job and wasn’t sure if she should accept it. I emailed her back some reflection points about the commute, sense of community, what it might mean to go part time so she could consider those.

A big change on a personal level normally needs some time for reflection and as a trusted colleague, I can be a sounding board for project team members or mentees to talk through their reflections in a safe space, if they prefer to do that rather than reflecting alone.

You can also help people reflect on their skills and the area in which they would like to develop. While mentoring another colleague, we’ve talked often about career progression and what her next steps might be, and now I have an insight into where she wants to go, I can help her uncover the skills that would let her be a success in that future role.

Offer direction

When people need a clear route forward through the change, as a project manager, you can offer clarity. For example, if a colleague is struggling, you can say, “Have you thought about bringing that up with your manager/going on that training course” or something similar.

This could help a colleague with a smooth transition to whatever the new ways of working might be.

Offer knowledge

Sometimes given the project leadership role you have, you’ll have access to information that others don’t have. For example, I was able to connect a project team to the appropriate operational expert who needed to sign off on the work before it went live, as they weren’t aware of that required step.

Even small things like that can help with successful change management for your project. Remember, these