The Stakeholder Salience Model and How to Use It

This blog is reader-supported. When you purchase something through an affiliate link on this site, I may earn some coffee money. Thanks! Learn more.

What is the stakeholder salience model?

The stakeholder saliency model was proposed by Mitchell, Agle and Wood (1997). They define salience as:

the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims.

Their model looks at how vocal, visible and important a stakeholder is. Those dimensions help you identify the stakeholders who should get more of your attention.

Project stakeholder management and saliency

Project management relies on people: you need the project team to get things done, and that team might include members of different stakeholder groups. It’s common to have a core team of people who work daily (or at least regularly) on the project, and then a wider stakeholder community.

The saliency model is a tool you can use as part of stakeholder analysis, management, and engagement. It’s a way of categorizing stakeholders so you can evaluate the best way to involve them in the project.

There are three elements to consider, which together highlight the saliency of a stakeholder: in other words, how much priority you should give that stakeholder.

The three considerations are:

- Legitimacy

- Power

- Urgency.

Let’s look at each of those.

Legitimacy

This is a measure of how much of a ‘right’ the stakeholder has to make requests of the project.

Legitimate stakeholders can have a claim over the way the project is carried out can be based on a contract, legal right, moral interest, or some other claim to authority.

The strategic management layer in an organization is likely to have a say in how the project proceeds. Key customers or clients are also likely to have high legitimacy.

Power

Power is a measure of how much influence they have over actions and outcomes. Their power could derive from hierarchical status or prestige within the organization, money invested from a particular shareholder, ownership of resources required to successfully deliver the outcome, or similar.

Larger projects are likely to have higher numbers of people with power involved because they tend to attract greater corporate governance and oversight – so the top management likes to know what is going on.

Examples of stakeholders with high power are the sponsor, the CEO and the client.

Urgency

This is a measure of how much immediate attention they demand and how unacceptable a delay in response/action is to the stakeholder.

The expectation of high urgency can result from some kind of ownership, previous experience where urgent action was taken that leads to continued expectations of comparable response times, a time-sensitive problem that creates exposure for the stakeholder, or similar.

For example, how often are they likely to bring you urgent issues? Things that can’t wait?

Again, sponsors, clients and senior management are likely to score highly for urgency. Regulatory agencies and compliance teams might also have the right to demand immediate action.

Together, an assessment of these three elements can tell you how engaged a stakeholder is or will be in the work and how they could influence the project. This is useful information for tailoring your engagement activities and working out with whom to invest your time.

How the dimensions overlap

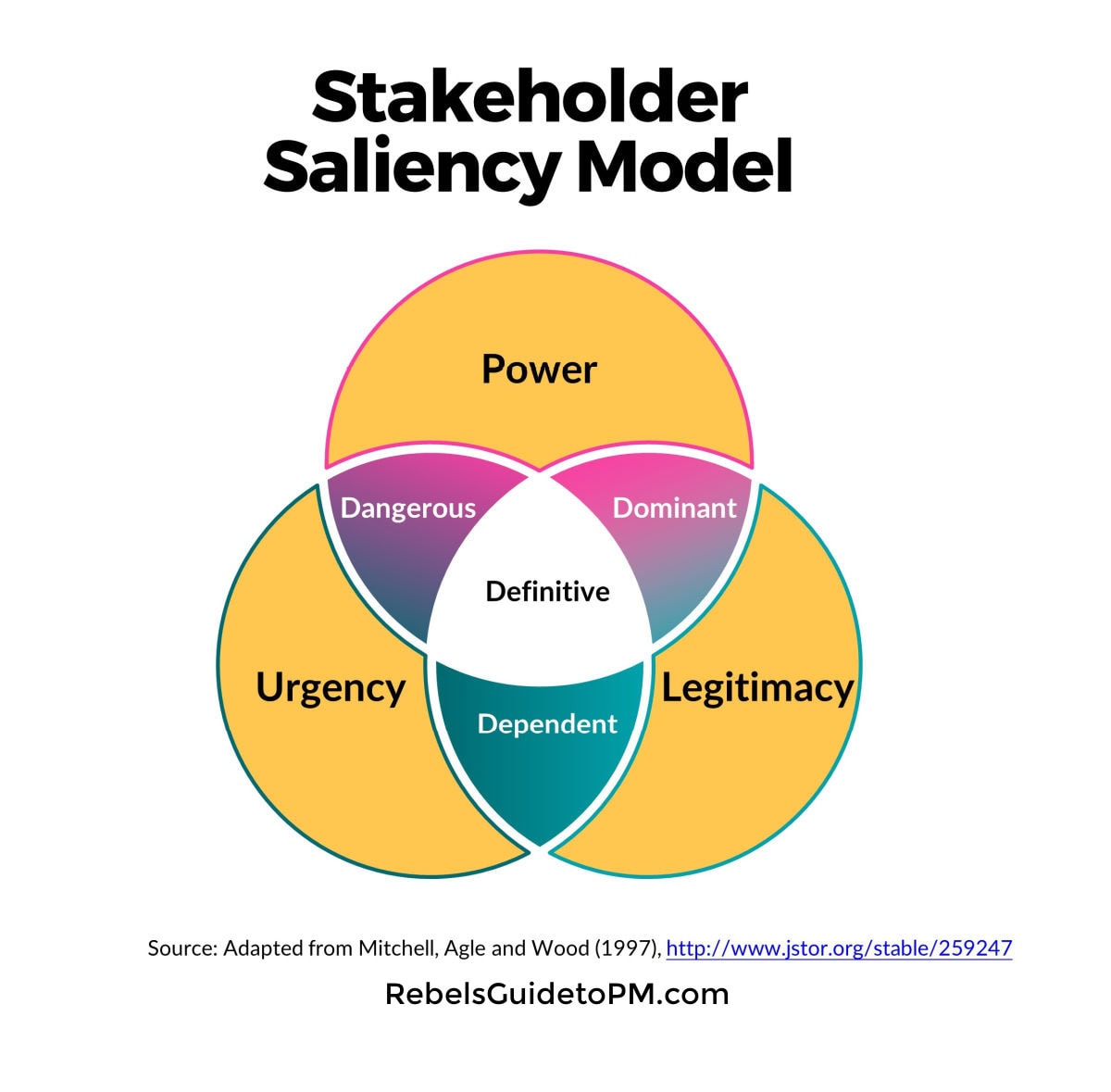

The picture shows how power, legitimacy, and urgency overlap to give stakeholders more or less saliency.

Project managers love a good Venn diagram!

Stakeholders that fall into areas where they have two or three elements of saliency are the ones to be most aware of and to spend the most time with.

Mitchell, Agle, and Wood define these salient stakeholders as follows.

Dominant stakeholders

This group has high power and also high legitimacy to influence the project. An example would be the board of a company. The blend of power and legitimacy means they can act on their intentions, should they ever want to.

They might not spend much time on the project, but you know about it when they want to get involved.

Dangerous stakeholders

This group has high power and also expects their needs to be met with a high degree of urgency. However, they have no legitimate claim over the project.

The researchers point out that project stakeholders in this group, for example, pressure groups can use coercive power and unlawful tactics to draw attention to their interest in the project.

Dependent stakeholders

This group has legitimacy and urgency but lacks real power to influence the direction of the project. An example would be the future process owner who will be responsible for running the activities resulting from the project’s deliverables.

If you work in projects for local governments, for example, you might find that lobby groups, local community groups, or local residents fall into this category.

They have a legitimate claim to influence the project as the outcome is going to impact their environment. They want their views to be heard in a timely fashion. But they don’t really have any power to influence the direction of the work because they are not employed by the contractors.

They are ‘dependent’ because they depend on the power of others to generate action at this time.

Definitive stakeholders

This group meets all the criteria for saliency. They have high power in the situation, they have a legitimate claim over the project and they have a claim to urgency.

For example, your sponsor.

Together this gives them an immediate mandate for priority action on the project. Typically, this situation occurs when a dominant stakeholder wants something done and gains urgency as a result.

Small projects may only have definitive stakeholders: perhaps just you and a manager.

Non-stakeholders

They also define a group of people who don’t meet any of the criteria and are therefore not stakeholders.

I would advise caution when using this label because often you simply haven’t identified them as stakeholders yet – they might be at some point.

There’s also a risk attached to labeling everyone else as non-stakeholders. Perhaps you simply haven’t identified them yet.

Other types of stakeholders

The model does talk about other groups – what happens if someone falls into the bracket where they only meet the criteria of urgency, for example. If you want to look them up, these are:

- Dormant stakeholders

- Expectant stakeholders

- Latent stakeholders.

My personal view is that in a business context, given how little time we have to engage all the stakeholders, it’s better to focus on the individuals and groups who tick two or more boxes. The reality of managing projects is that you simply don’t have the time to go through a consultation process and do the analysis for everyone.

Your choice, though.

How to use the salience model

So what are the practical implications for the model of stakeholder salience?

Understanding stakeholder saliency is useful because it helps you identify how to spend your limited resources. You have limited time, and you can make the most of that by applying different levels of stakeholder engagement to different people.

Stakeholder relationships are time-consuming, so it’s worth investing your energy where it is going to have the greatest effect.

Look through your analysis and identify the individuals and groups who are going to benefit most from your time. Prioritize the definitive stakeholders as they tick all the boxes.

Then look at the other groups. There might be important stakeholders hidden away in other categories. Don’t let the model become a replacement for common sense.

However, remember, stakeholders can move between the categories as the project and the situation evolve.

Power, urgency, and legitimacy can be lost and gained slowly over time, or in a moment. Keep your analysis under review and switch up your actions accordingly, creating a stakeholder management strategy that fully engages your community to the best of your ability.

This is an edited extract from Engaging Stakeholders on Projects: How to harness people power by Elizabeth Harrin (APM, 2020).

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R. and Wood, D. J. (1997) ‘Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts’, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22 (4), pp. 853-886.